TURKEY

With Syrian Refugees in Iskenderun

This morning three of us went to one of the nearby schools for Syrian refugee kids, where we may get involved. We arrived and sat down in one of the 10 “container” rooms that the school had donated for classrooms and offices, and we were soon joined by a Syrian woman in her late 6

This morning three of us went to one of the nearby schools for Syrian refugee kids, where we may get involved. We arrived and sat down in one of the 10 “container” rooms that the school had donated for classrooms and offices, and we were soon joined by a Syrian woman in her late 6 0s. I assumed we might have some awkward silence between us until a translator arrived, but she opened her mouth and out came an English more beautiful and properly spoken than my own. She exuded a glow and purposefulness that, paired with her covered head and hunched over posture, had me think I had just met the Syrian Mother Theresa.

0s. I assumed we might have some awkward silence between us until a translator arrived, but she opened her mouth and out came an English more beautiful and properly spoken than my own. She exuded a glow and purposefulness that, paired with her covered head and hunched over posture, had me think I had just met the Syrian Mother Theresa.

The Headmistress of this make-shift school, she had studied English literature at Aleppo University, as it was her lifelong dream to learn and speak English. We were then joined by the director, Dr. Mahmoud, who has what I would call a certain “weight” or gravitas to him. He sat down then learned forward to passionately described what the situation is and what the school needs — very clearly and specifically.

The Headmistress of this make-shift school, she had studied English literature at Aleppo University, as it was her lifelong dream to learn and speak English. We were then joined by the director, Dr. Mahmoud, who has what I would call a certain “weight” or gravitas to him. He sat down then learned forward to passionately described what the situation is and what the school needs — very clearly and specifically.

The matriarch, Wafaa, translated for the director as I sat mesmerized. As we have learned, these Syrian children, 1,000s in this town alone, are burdened by the weight of what they have been through. They have lost their fathers, their relatives, and have seen horrible things — war at first hand — and now live in a foreign country. Some schools are in more need than others, but the need for laughter and creative expression is at the top of the list. As I heard others’ reports today, tears flowed and my heart warmed and burned, realizing that we’ve been put in the position to provide this.

Dr. Mahmoud told us that many of the children have “all this” going on inside of them, as he gesticulated something like a hurricane in his chest area. Their “art” reflects the tragedies they have witnessed. He explained, ”We want to help them get that traumatic energy ‘out,’ by dancing, singing, laughing, through creativity, playing, jumping around, and NOT by turning to pick up a gun and fight.” My hope is that through our time here we can help these kids make some movement in this direction, toward a chance to spend some of what’s left of their childhood doing what we’d hope for all kids to have and experience.

The school directors were enthusiastic about the possibility of our puppet show performance as well as our visiting classes to teach English and art. Now the question is how to perform, at this one school alone, for the 1,000+ kids, with no indoor space that holds more than 30, and max 120 in their gravel courtyard…

We had spoken on the way to the school about looking out to see the bigger picture, to take note of what’s needed here as opposed to looking out for our own pleasure. Afte r being with the Syrians most of the day today, I realized that I’d had no feelings of hunger, had put no attention on my usual physical aches and pains… it felt like my eyeballs and ears were extending out of me taking in all I could to better know how to respond to what might be needed. It was/is incredibly enlivening. Very different than the “normal” state I often dwell in back home, where I take on a sense of purpose only when it pleases me and when it fits on my eating / sleeping schedule, and only for the amount of time that I feel like it.

r being with the Syrians most of the day today, I realized that I’d had no feelings of hunger, had put no attention on my usual physical aches and pains… it felt like my eyeballs and ears were extending out of me taking in all I could to better know how to respond to what might be needed. It was/is incredibly enlivening. Very different than the “normal” state I often dwell in back home, where I take on a sense of purpose only when it pleases me and when it fits on my eating / sleeping schedule, and only for the amount of time that I feel like it.

So here I sit, with 5 friends, outside at a cafe on a quiet night on the bank of the Mediterranean Sea, talking, reflecting, writing about the “start” of this adventure, watching and listening to the waves gently lap on the shore of the bay, counting my blessings.

Article For Our Local Newspaper

The month of November 2013 I was in Turkey near the Syrian border. I went with a group of 18 friends who formed a non-profit 25 years ago, organizing to bring aid to people in great need. They have been to many countries and this was my first trip with them. This type of charitable endeavor fulfills a lifelong dream of mine and I want to share the impact of my experience.

Six Syrian refugee schools have been set up in the last year in the city of Iskenderun, 25 miles from the Syrian border, and 75 miles away from the intense fighting in Aleppo. The newest and largest has over 850 students, opened in an industrial area using donated cargo containers as classrooms. The schools are privately funded by the Syrian refugees, using their own savings and gathering donations to take in the growing number of children. Our main objective was to instill the feeling of hope that other people in the world know what is happening to them and care. We performed puppet shows which brought roars of laughter and excitement to the children at each school. They were absolutely delighted and so were we.

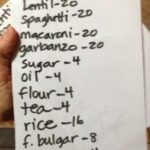

We went into the classes and taught English and art. We bought and passed out school supplies. We also bought food staples and toys for a number of the neediest families. I was amazed how the Turkish people have accepted the burden of hundreds of thousands of refugees with such generosity, graciousness and compassion. The manager of the local supermarket, for example, went out of his way to have large quantities of food delivered to his store for us to pick up, at cost, when he heard who the food was intended for. The Syrians were warm and welcoming despite the enormity of the suffering they’ve endured. They were astonished and grateful that people had come so far to help them.

Like most of us, it didn’t occur to me that I was capable of helping in such an overwhelming crisis. I had been hearing about and ignoring the Syrian refugee crisis for over 2 years not realizing that I could make a difference. Even with a small group of people we were able to have a significant impact on a number of lives. The Syrians we met now know there are people that care about what is happening to them, they are not alone. My greatest wish for the Syrian refugees is for that hope to stay alive, helping them recover from the trauma they have suffered, and for all of us to know that a little from each of us adds up to a lot. We can both provide aid and inspire hope.

Like most of us, it didn’t occur to me that I was capable of helping in such an overwhelming crisis. I had been hearing about and ignoring the Syrian refugee crisis for over 2 years not realizing that I could make a difference. Even with a small group of people we were able to have a significant impact on a number of lives. The Syrians we met now know there are people that care about what is happening to them, they are not alone. My greatest wish for the Syrian refugees is for that hope to stay alive, helping them recover from the trauma they have suffered, and for all of us to know that a little from each of us adds up to a lot. We can both provide aid and inspire hope.

For Our Local Newspaper

While volunteer ing at schools for Syrian refugees in Iskenderun, Turkey, last November, I daily saw women in the streets and markets dressed head to toe in black, with only their eyes showing. I wondered about the lives of these veiled women but did not imagine any possibility of interacting with them.

ing at schools for Syrian refugees in Iskenderun, Turkey, last November, I daily saw women in the streets and markets dressed head to toe in black, with only their eyes showing. I wondered about the lives of these veiled women but did not imagine any possibility of interacting with them.

One day, in an English class where I volunteered, there was a gentle knock and the door opened. The founder and principal of this school had mentioned a psychologist who sat in on classes to evaluate how each student was coping with their new refugee status and challenging educational environment. Wearing a black head scarf and a full-length black abaya cloak, Lamis entered. I was struck by her quiet, mature demeanor as she introduced herself and asked in flawless English if she could observe.

Having no idea what restrictions this 24-year-old woman might have on moving around with a foreigner, I nevertheless one day asked if we could talk sometime. She replied, “Yes,” enthusiastically and said I could ask anything I wanted.

We met the next day after classes. I was surprised to see that she was now wearing long black gloves, as well as niqab — a face veil — revealing only her eyes. She waved down a neighbor’s car. We squeezed in with him, two women and three kids.

In town, Lamis led me into a kebab restaurant, lowering her niqab to order from the waiter. He asked her to translate to me how upset Syrians were when Obama said he would take out Assad and then reneged. We talked about her family’s departure from Syria; about Aleppo University; the Koran (“Please, say what you think!” she said earnestly); the price of housing in the U.S.; and about her husband.

She explained that since her teens, she had worn the abaya for comfort and by choice. Through college she had also worn the niqab. No professor ever saw her face. Now, in Turkey, the founder of the school will not allow face veiling. When I inquired, she replied, “Once I make a change, I do not regret and do not look back.”

We took a bus to her apartment. She was late for her prayers. Waiting for her in a room with bare walls, two couches and a Syrian news feed on TV, I entertained her 2-year-old and mother-in-law by making balloon animals. Lamis reappeared, startling me once again — she wore a pink sweat suit with long hair in a pony tail. Suddenly, she looked even younger than 24, like any college student, like an old friend at UC Berkeley. For our goodbye photo, she slipped the abaya back on.

I am grateful for this day spent learning about the situation and perspective of one remarkable young refugee. She is inspiring and caring for the even younger ones, who wait patiently — though perhaps in vain — for their return to a free Syria. I wish Lamis and each of these children all the best.